Previous Exhibition: The Making of Medieval Manuscripts

As our last exhibition sought to explore the history of the book from scroll to codex, papyri to paper, our current exhibition seeks to delve specifically into the world of medieval books and their production. Each case focuses on a single aspect of the production of a medieval manuscript, from the preparation of the parchment in the first case, through to the application of gold pigments and paints in the sixth. The manuscripts on display have been specifically selected from the Parker's collections to highlight each stage in the production of a medieval manuscript, while many of the tools and raw materials have been kindly loaned to the Library from the personal collection of Patricia Lovett MBE, a professional illuminator, calligrapher and long-term friend of the Parker Library. Credit is also due to the British Library, along with Patricia Lovett, for the creation of the videos embedded here that illustrate how these tools and raw materials come together in the process of making of medieval manuscripts.

Case 1: Parchment

Most medieval books were written on parchment, made from animal skin, usually from cows and sheep but also goats. It was suitable, available and durable. The parchment-maker first washed the skins then soaked them in vats of lime and water to artificially loosen the hair before scraping and shaving off both hair and any remaining flesh from both sides. The pelts were then washed a second time and tied to a wooden frame to dry, stretched taut and repeatedly scraped using a crescent-shaped knife called a lunellum, paring the skins ever thinner. Finally the dry, thin, opaque parchment was released to be cut into large rectangular sheets and passed on to scribes, who would then rub them with chalk, pounce or pumice before their surfaces were finally ready to be written on.

The Bury Bible (MS 2iii)

Prices of parchment of course varied greatly, but top-quality parchment could be extremely expensive, often representing the second largest expense after gold in making a book. The majestic twelfth-century ‘giant’ Bury Bible (MS 2) was clearly commissioned to be, in all ways, spectacular. The Abbey’s accounts chronicle its production in unusual detail, recording expenses incurred, including hiring a highly-skilled professional artist named Master Hugo to provide the book’s magnificent decoration and illumination, but also significant payments for procuring parchment of the highest quality from either Ireland or Scotland (‘Scotiae’).

Case 2: Pricking

Having cut the parchment sheets to the desired size, each sheet needed to be pricked in preparation for being ruled. Done with a small, spiked wheel or pair of callipers, the scribe or another member of the scriptorium or monastic community, would make equally spaced holes along the outer margins of each bifolium.

Normally these holes are on the edges of each page; however, in some earlier manuscripts, such as MS 286, The Gospels of St Augustine, the prick holes can be found in the centre of each page as well as along the edges (trying using the ZPR viewer to zoom in on St. Luke's face, see the holes?). Variations in the pattern of pricking, and where it is located on a page, can help scholars date a manuscript and, perhaps, identify where it was made

Additionally, the spacing of the holes can provide information about the intended owner of a manuscript. If the holes were made closely together, the writing was intended to be small and compact, suggesting that the original book was intended to be an economical production, while a greater space between the holes suggests a more deluxe manuscript intended to be written in a more elaborate script. On occasion, it may be difficult to see the prick holes as the edges of the parchment were often cut off when the book was bound. In MS 387, the prick holes are still clearly apparent, though in the earlier MS 221, it is clear that the manuscript has been cut down, resulting in the loss of visible prick holes on some pages of the manuscript.

CASE 3: RULING

After each bifolium had been pricked, the scribe used a ruler to connect each pricked hole on one side of the bifolium to the corresponding hole on the other side in order to form the lines that the scribe would then follow while writing the book. Early books tended to be lined in ‘hard-point’, which means that the lines were formed as an indentation in the page, rather than in lead or ink. Later, lead ruling comes to be the norm, which can be identified by its ‘pencil-like’ appearance. By the late fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, some very deluxe manuscripts are even ruled in ink, and the ruling itself came to form part of their elaborate decorative schema. Though the ideas behind pricking and ruling appear simple, the two manuscripts in this case illustrate just how complex some of the patterns could be.

In MS 75, the lead ruling is the same throughout the page, though the scribe is consciously adjusting the size and spacing of his script to ensure that the smaller text, the gloss, or commentary, continuously relates to the larger text, Psalm 101.

Though more commonly thought of in the context of medieval pigments such as 'lead white' or 'red lead', could also be used in its raw form to connect the prick-holes on each side of a bifolium.

The second manuscript in this case is truly a triumph of the ruler’s art. At 20,472 words, the Gospel of Luke is the longest in Bible, almost double the length of the Gospel of Mark, which is a terse 11,724 words long. However, despite the differences in their respective lengths, in MS 48 each of the four Gospel texts begin and end on the same line, purely through varying the ruled widths of each of the four columns.

CASE 4: WRITING AND SCRIBES

Manuscripts were written by hand. The familiar image of the medieval scribe copying texts with a quill pen, as witnessed here in MS 389, offers a detailed and accurate depiction of the process and tools of medieval writing. The scribe’s pen (held here in his right hand) was generally made from the feather of a goose or a swan. The feather was fashioned into a quill through trimming almost all its barbs away, toughening the tubular barrel for use by soaking in water then hardening in hot sand, then ‘hollowing out’ its core and cutting its tip to a nib using a short, sharp penknife.

The scribe kept his knife in his other hand as he wrote, as seen above, for it served many functions in the writing process: besides using it to sharpen his quill, he used his knife to erase his mistakes – by swiftly but gently scraping the ink from the page – and also to steady the pages as he wrote. His writing desk was angled at 45 degrees to aid the flow of ink from his quill, which he loaded with ink through repeatedly dipping into an inkhorn. This ink might have been made according to various recipes, but was probably iron-gall ink, made by mixing a solution of crushed-up oak galls with rainwater and gum Arabic.

A single manuscript could be copied by several scribes for speed of production, as in the case of MS 140, each of whose four Gospel texts was copied by a different scribe. The one responsible for Matthew names himself as ‘Ælfric’, a monk at Bath Abbey who, in his Latin colophon, shown here, asks that ‘he who wrote this book may live in peace in this world and the next’.

CASE 5: COLOUR

The vibrant colours of medieval manuscripts have their origin in the plants, animals, and minerals of the natural world. In the case of plants, woad leaves (first above) and madder root (second) form a deep blue and light pink respectively, while the shells of a beetle when dried and crushed result in Carmine Red. The enigmatic Dragon’s Blood (third), supposedly derived from the blood spilt as elephants and dragons fought to the death, classically is derived from tree resin, principally those on the island of Socotra off the coast of Yemen. Minerals, such as verdigris (fourth) and malachite (fifth) could both be ground down to both provide vibrant green hues, but for the deepest of blue, suitable for the Virgin’s robe or heaven itself, lapis lazuli (sixth) was ground down to a fine powder. However, unlike verdigris or woad, both of which were plentiful in Europe, lapis lazuli needed to be imported from the mountains of northern Afghanistan – likely via the silk road, first appearing in European manuscripts in the late 9th century – and making it more expensive than gold.

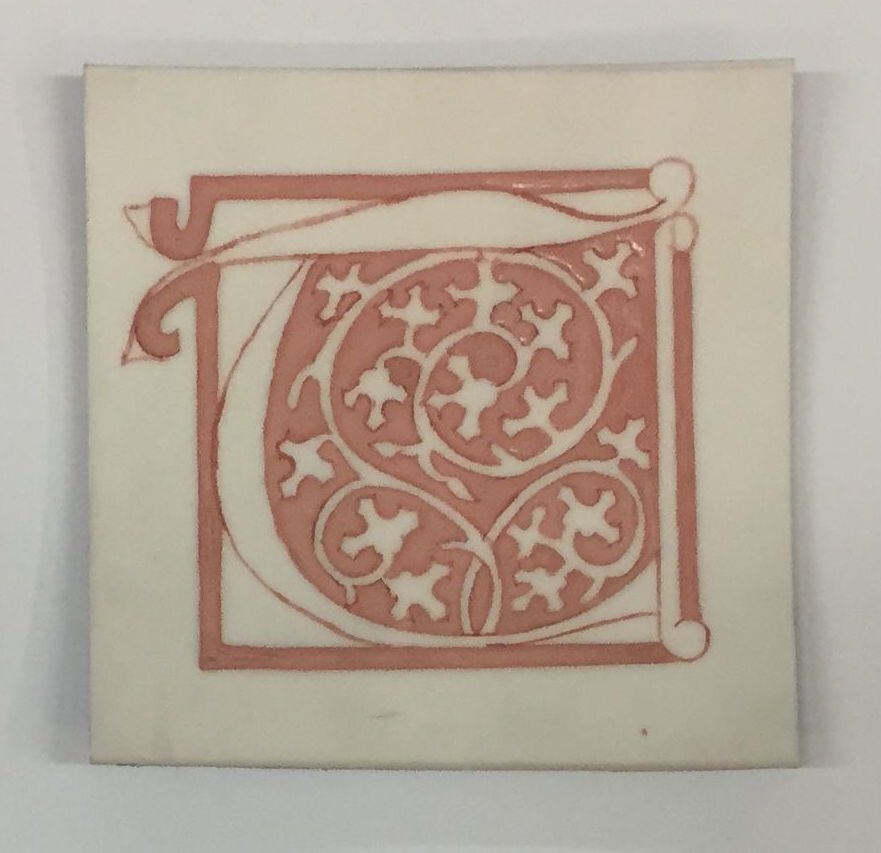

In order to turn pigments into paint, each raw material would be ground finely, perhaps by an apprentice or a younger member of a monastic community. The ground pigment would then be mixed with a binding agent – commonly egg white or egg yolk – to create a vibrant colour, suitable for use in the most elaborate of miniatures or for simply stunning capital letters.

The opening page of the final litany in this manuscript shows off an astonishing array of colours, from the brilliant azurite blue, to the orange minium, the green verdigris, and red lead for the upper portion of the text.

CASE 6: GOLD AND ILLUMINATION

Most medieval manuscripts are decorated in some way. This may mean simply the addition of coloured inks or the penwork embellishment of important ‘capital’ letters in the text, but might equally mean the inclusion of illustrations, diagrams, pictures or initials. Nevertheless, only the presence of gold (or, less frequently, silver) qualifies these to be called ‘illuminated manuscripts’. The following case provides a step-by-step explanation of the process through which the gold was applied, but this pair of manuscripts provide glorious examples of the kinds of different uses that medieval illuminators made of gold – in sheet, powdered or ‘liquid’ forms – to illuminate their decorations.

Whether in full-page frontispiece pictures (MS 61) or through the radiant embellishment of elaborate miniatures and gilded borders (MS 79), gold announces that these manuscripts were deluxe commissions designed both to be beautiful and display the status of their owners. Within the order of stages in which medieval artists and illuminators compiled these glorious illuminated decorations, the gold was applied first (for reasons that will become clear) but after a thousand years its shine can remain as bright and enchanting as the day it was added, for unlike silver, gold cannot tarnish. Its sparkle will never fade and will delight the eye and warm the heart forever.

CASE 7: THE SEQUENCE OF MANUSCRIPT ILLUMINATION

The prepared design is transferred to the vellum and the outline reinforced by minium. Minium is roasted white lead, and because miniatures were outlines by minium they are called miniatures. They are not called miniatures because they are small - look at the illuminations in the Bury Bible behind you - but because they are outlined in minium. However, because they were often small, this became the word we now use.

A mixture of slaked plaster of Paris, lead carbonate (flake white), gums and glues is applied to the surface using a quill only where there is to be gold. This raises the gold leaf from the surface and so it catches the light and ‘illuminates’ the book even more.

Tissue thin almost pure gold leaf (23.5ct) is applied to the gesso, and polished with a burnisher which brings up the shine. Burnishers are often made of polished metal such as haematite or psilomelanite, or polished agate stones can be shaped and polished. In medieval times, they used animal teeth, and a burnisher today is still called a dog tooth burnisher, even though no teeth are used!

The base colours are applied using egg tempera. Pigments (in this case cinnabar and ultramarine) are mixed with an adhesive, such as egg yolk or beaten egg white and applied.

Shades and tints are added which give the image some depth.

White highlights, usually using ceruse (white lead) are applied.